Jonathan Reeder’s Choice: Willem Elsschot and Mathijs Deen

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. This time you will read the choice of Jonathan Reeder, who translated work by the likes of Martin Michael Driessen, Marjolijn van Heemstra, Roger Van de Velde, Rodaan Al Galidi, Peter Buwalda and A.F. Th. van der Heijden.

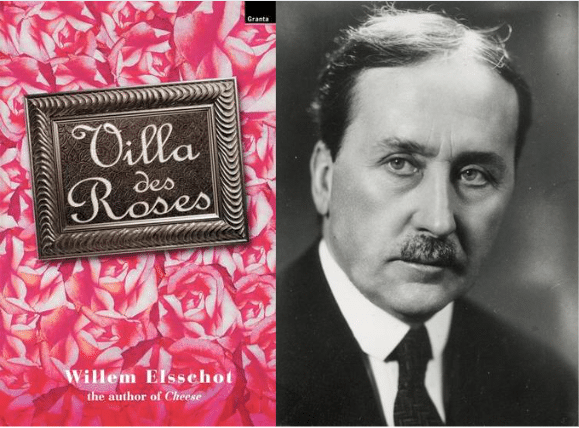

Must-read: ‘Villa des Roses’ by Willem Elsschot

Since English-speaking readers might not have a firm idea about the Belgium–Netherlands cultural divide, I would start by recommending a Flemish (ah, there’s the first bit of confusion for the English reader) author, one whose style, setting, and themes distinguish themselves as ‘Flemish’: Tom Lanoye, Erwin Mortier, Annelies Verbeke, Dimitri Verhulst.

But let’s make my must-read the very first Flemish book I myself read some twenty-five years ago: Willem Elsschot’s comic novella Villa des Roses, first published in 1913. It’s set in a down-at-heel boarding house in Paris’s 17th arrondissement, run by one Madame Brulot, who lavishes more attention on her pet monkey Chico than on her long-suffering husband, a retired notary. Their boarders include a half-senile old lady, a suicidal Frenchman, assorted East European women, and a warm-hearted Norwegian. Madame Brulot doesn’t exactly cheat her lodgers, but neither is she completely square with them. She will have nothing to do with newfangled conveniences like electricity or a bathroom; she keeps chickens in the yard but sells the eggs in town, sneaking in cheaper, foreign-bought ones to tout at breakfast; the wine at dinner is watered down.

Villa des Roses was Elsschot’s debut, and its gentle satire foreshadows his later novels, all twentieth-century classics: Lijmen/Het Been (Soft Soap/The Leg, translated by Alex Brotherton) and Kaas (Cheese, translated by Paul Vincent), all set in Belgium and with the deadpan humor typical of so many Flemish writers. As Paul Vincent, the translator of Villa des Roses, says in his introduction, ‘black humor and compassion are present in equal measure.’

Willem Elsschot, Villa des Roses, translated from the Dutch by Paul Vincent, Granta, 2003, 144 pages

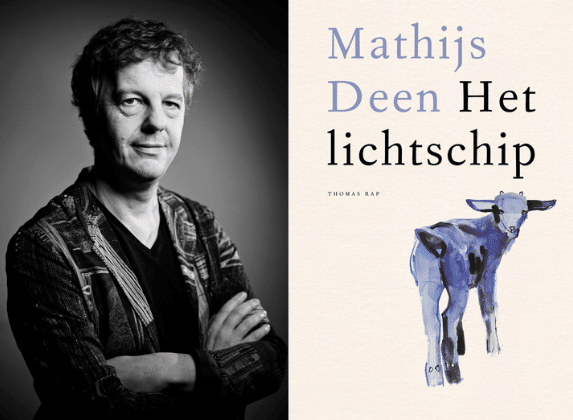

To be translated: ‘Het lichtschip’ by Mathijs Deen

© Merlijn Doomernik

One modern Dutch book absolutely deserving of an English translation is Mathijs Deen’s novella Het lichtschip (The Lightship,

2020). Deen is a radio producer and a writer of non-fiction, short stories and novels. Not only is his fiction exceptionally inventive, with never a word too many, Deen has a keen, compassionate eye for the subtleties and frailties of human nature. Take the man who sits meticulously, silently, peeling potatoes in one of the miniatures from the collection Brutus is Hungry: ‘Forty years now his father is dead, but he still tries his best.’

But back to Het lichtschip: for the crew of the lightship Texel, life is predictable, the living quarters cramped, the wages meager. During their four-week stint anchored in the middle of the North Sea, the men keep watch, take weather measurements, and note the names of passing cargo ships. At the center of this intimate company is the ship’s cook, Lammert, whose youth was darkened by internment in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp on Java. The old trauma rears its head now and again.

Lammert’s three regular meals a day offer reassurance and routine in an otherwise isolated, tedious existence on the ship. Until the day he brings – flouting regulations – a live buckling on board which he intends to fatten and slaughter for his favorite stew, a recipe of his mother’s. The sprightly young animal disrupts the ship’s daily groove. What begins as a welcome break in the mundane grind soon arouses latent fears, sows discord, and claims victims.

In just over a hundred pages, Deen brings us intimately and movingly close to Lammert, but also to his village neighbor Beitske, his fellow crewman Snoek, and the nameless baby goat.

Mathijs Deen, Het lichtschip, Thomas Rap, 2020, 128 pages

Excerpt from ‘Het lichtschip’, translated by Jonathan Reeder

He opened the trunk and sniffed the air that rose up from his past. With both hands he took the box with his father’s sextant, set it mindfully onto the floor planks next to him, lifted two batiked sheets and looked into the darkness in search of his mother’s cookbook that was stowed away in there somewhere. He picked it up and slid it under his shirt, replaced the batiks, laid the sextant on top of them, closed the trunk, and went back down the ladder.

In the kitchen he laid the cookbook next to his plate. He ate his bread, got up, rinsed the plate and the knife, wiped the crumbs from the table into the palm of his hand, threw them through the half-opened door into the yard, put away the plate and knife, sat back down, and opened the cookbook.

In among the stamppot recipes, his mother had slid a few sheets of sparsely handwritten paper. Time had faded the ink and yellowed the paper. Lammert got up, walked over to his desk to fetch his reading glasses, and stood in the open kitchen door with the pages in his hand. His mother’s handwriting did not leave him cold. He cursed under his breath and read. He knew the first lines by heart:

For little Lammert, to be prepared according to his own taste and discretion. These are the basic ingredients, assembled in camp SOLO and AMBARAWA by your mother and other women.

Approximately two servings.

‘Approximately two servings,’ he grumbled, shook his head, and read further. The letters were in the impatient handwriting so familiar to him. He leafed through the five sheets until he found what he was looking for: gule kambing. Goat stew. He studied the list of ingredients, repeated them in a whisper, until he had not only deciphered the words, but understood how the recipe worked. He guardedly forged his way through the list, searching, as if to retrieve a treasure from under a dragon. There she was again, his mother, glowering at him from behind the recipe’s words, absorbed in her own woes and suffering. He saw what she had exaggerated, what was the consequence of homesickness and what of hunger, where she boasted, where she ran off at the mouth, where she was aggrieved or overly begrudging. There was always something in the recipe that spoiled it, that made life even more difficult than it already was.

He went inside, took a notebook, and began to write.

The translation of this excerpt by Jonathan Reeder in 2021 was kindly supported by the Dutch Foundation for Literature.